A lifeline for entrepreneurs

Tomme Beevas has grown his passion for Jamaican cooking from informal backyard barbecues with his neighbors to a multimillion-dollar business. The success of Pimento Jamaican Kitchen, he says, would not have been possible without the support of Hennepin County’s Open to Business program.

Backyard beginnings

Grilling the traditional food he grew up on in Kingston, Jamaica, was initially a way for Beevas to unwind from working as a director of global community relations at Cargill. “It was a dream position, helping to feed people all around the world,” he says.

But it was feeding people in his own backyard that kick-started his venture into the restaurant business. The island-spiced aromas from his south Minneapolis grill started to attract neighbors and friends. His yard soon became such a hot spot to eat, so he decided to turn it into a business.

He teamed up with his next-door neighbor, Yoni Reinharz, a local hip hop artist known for his role in launching the Jewish-Jamaican rap genre. Together, they started bringing their classic Jamaican fare to local events like the Uptown Art Fair and Pride Festival.

Next, they got picked up by the Food Network show "Food Court Wars." They won. The prize money helped launch their first brick-and-mortar location of Pimento Jamaican Kitchen at the Burnsville Center in 2013. Beevas soon decided to leave his job at Cargill, realizing that growing Pimento would require his full attention.

It would also require financing and support that banks were hesitant to provide.

An unsavory wake-up call

“With all the right paperwork, all the profitability, all the right resumes, we just have not been able to get funding from traditional banks,” he says.

Beevas says he recognizes banks view restaurants as a high-risk industry. He also knows people of color continue to face particular challenges accessing business financing and loans.

“Banks will not lend to restaurants and, let’s be honest, to people of color. It’s still a challenge,” he said.

There are persistent disparities in access to capital between minority-owned businesses and their White counterparts across the country.

While the growth in number of minority-owned businesses across the nation has far outpaced the growth in non-minority businesses, small minority-owned businesses are still denied loans almost three times as often as non-minority-owned businesses of the same size. When they are able to secure loans, they are for lesser amounts and with significantly higher interest rates, according to a recent study by the Minority Business Development Agency of the U.S. Department of Commerce.

"A literal lifeline"

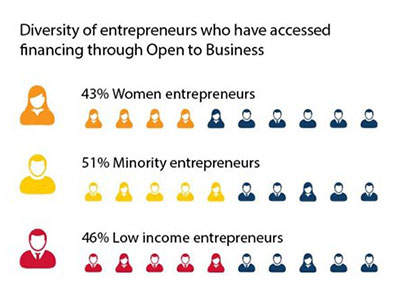

Programs like Open to Business are stepping up to provide financing and capital to minority-owned businesses. More than 50% of businesses accessing financing through the program are run by minority entrepreneurs; 43% by women and 46% by low-income business owners.

Beevas calls the Open to Business program Pimento’s “literal lifeline.” The financing and technical support he was able to access through the program and others like it have helped him open a new location in St. Paul and add a rum bar and event space onto Pimento’s Minneapolis Eat Street location. Pimento also operates a successful food truck and is expanding its space at TCF Bank Stadium.

Before participating in Open to Business, Pimento was making about $200,000 a year — an impressive early return for a new restaurant. Many restaurants spend years in the red before turning a profit. Eighteen months after working with Open to Business, profits had risen to $1.5 million. If they continue to meet goals and projections, the company will be making $6 million annually by 2020, Beevas says.

The Open to Business program has been a lifeline for many other businesses too. From 2012 to 2017, the program provided technical support to 1,900 businesses and $7.8 million in direct or facilitated capital to small businesses, leveraging another $51 million in financing from other sources.

Lost economic potential

Pimento’s success leads Beevas to wonder how much regional economic potential is lost because entrepreneurs of color and immigrant business owners have trouble accessing financing to help them grow. He often mentions his grandmother, Sylvia “Baby Lue” Jones, who taught Beevas how to cook in her West Kingston kitchen. She eventually grew her own million-dollar business, despite having only a 3rd grade education.

“How many Baby Lues are we missing here in Minnesota simply because they’re a woman, person of color, immigrant, or are falling through the cracks?”

Economics of business equity

- There are roughly 44,000 businesses in Hennepin County

- 15% of Hennepin County businesses are minority-owned

- 7% of white people own a business*

- 2.5% of people of color own a business*

- 87,000 new jobs would be created if people of color owned businesses at the same rate as white people*

Data source: Center for Economic Inclusion

“These disparities are troubling, not only because entrepreneurship is an important pathway to wealth-building, but also because the region is missing out on the contributions that local businesses make to the whole community,” said Patricia Fitzgerald, Hennepin County manager of Community and Economic Development.

“From job creation, to increasing access to goods and services, individual and community wealth creation, and creating quality places people want to be — all of these are outcomes of supporting entrepreneurs and all are essential to Hennepin County’s economic stability and overall livability,” Fitzgerald said.

Beevas sees the potential. “One of the largest growing populations is immigrants and people of color. So naturally it makes sense to be ahead of the curve by offering resources to those groups so collectively we can grow our economy,” he said. “These programs are absolutely vital if we are going to continue to grow the Minnesota economy…if we are going to be building the next Cargills and the next General Mills of the world, it has to start with the newer immigrants — as was the case 150 years ago.”

Hennepin County is now building on the success of the Open to Business model by expanding our investment and programming to support small businesses through Elevate Business which offers no-cost expert advising, educational events and peer learning and other resources.

Learn more about Elevate Business.

This story reflects Hennepin County disparity reduction priorities in employment, income and justice.